Tale of Two Bibles

- Karen L Kurtz

- Dec 22, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: May 21, 2024

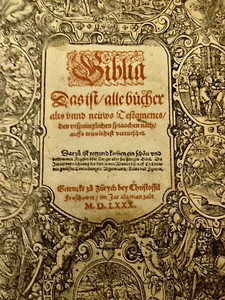

1580 Bible

A large, heavy Bible almost four and a half centuries old lay for decades in the archives of a historical society in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. No one knew who had donated it. Its text was Swiss German, which was not unusual in Pennsylvania where thousands of Swiss Mennonite refugees had fled in the 18th century. The Bible was one of the 1580 Froschauer editions, which had been banned in Switzerland because they were popular with the *Anabaptists. It was dangerous to be caught with a Froschauer Bible. Families hid them and didn't write any identifying personal inscriptions in them.

The first inscription was written 134 years after the Bible was published. It identifies the Kŭrtz family as the owners and records the marriage of Stefan and Madlina (Magdalina) Bärokji Kŭrtz in 1714, the year they left Switzerland as refugees for the Palatinate (SW Germany, today.) In the years that follow inscriptions are added for nine births and sad postscripts for five of them, who die in infancy.

The given names of their children have the -li suffix, a traditional spelling used for small children. One of two surviving sons, listed as “Hansli,” later inherited this family Bible. He was Hans (Johannes, “Hansli”) Kŭrtz, the older brother born in 1722.

1744 Bible

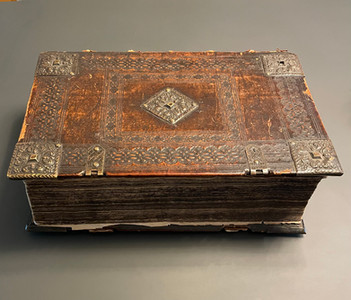

A second Bible belonged to the younger brother, my direct ancestor, Stefan (“Steffli”) Kŭrtz born in 1724. This heavy, pulpit-sized, leatherbound Bible lay for decades in my parents’ living room. It was lovingly cared for, treasured by our family, though we had little knowledge of its history at the time. It had been passed down through five generations to my father and then to me. Back in 1744 it was a newly published special edition—a reprint of an old, outlawed 1536 Froschauer Bible. It was purchased just before Stefan and his older brother set sail for Philadelphia.

One can hardly fathom how important those Bibles must have been to Hans and Stefan, who carried them across the Atlantic. Ships were crowded. To survive the journey passengers needed to bring as much preserved food as possible with them for the three-month voyage. They needed to pack the tools and goods required to start a new life. They needed woolens for the harsh winter ahead. Every item taken aboard had surely been measured and weighed against all the other possessions left behind; everything brought with them was essential. And so, one knows the Bibles were precious possessions, essential in their lives.

Hans was 22 and his brother, Stefan, was 20 in 1744, when they took a river boat North on the Rhine to Rotterdam and boarded a ship. It was quite late in the season to make the ocean crossing. Atlantic storms threatened in autumn, and a winter arrival in the new land was certainly not advisable. They booked onto an unusually small vessel, the Muscliffe Galley, which was a dubious choice for crossing the Atlantic. Galley-type ships were at risk if the seas grew rough. Why would they risk such a thing?

It was becoming more dangerous to stay in the Palatinate. The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI of Austria, had died and European powers were in the midst of the eight-year “War of the Austrian Succession.” The Palatinate villages were taxed heavily to help pay for the war. The pacifist anabaptists were charged extra fees to keep their young men from being conscripted into the army. Villagers were expected to quarter troops. Worse yet, an epidemic of a deadly cattle disease was spreading throughout Europe, wiping out the herds of struggling farmers.

Stefan and Hans’s father had died. Their mother most likely moved to their older sister’s home.

It was the worst of times. It was the best of times … for these two brothers to leave.

The ocean crossing and the pirate chase

The Muscliffe Galley sailed from Rotterdam in late September. It passed through a channel known as the Spithead, stopped at the customs house in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, and again in Poole, England to load cargo and provisions for the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Muscliffe Galley and the Kŭrtz brothers landed safely in Philadelphia thirteen weeks later on December 22, 1744.

Captain George Durrell was interviewed for Ben Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. Their trans-Atlantic passage had gotten off to a harrowing start, he said. Near the Isles of Scilly, as they left England, they’d been chased by French privateers (pirates.) He noted that a larger ship, the St. Andrew, had been captured by the pirates, but his own vessel outran them. Perhaps the nimble galley was a good choice, after all.

Pirate raids were common dangers, along with diseases, (such as smallpox, diphtheria, cholera, dysentery), which sometimes claimed as many as half the passengers en route. Ships were inspected at the Philadelphia dock, and sick passengers were transported to a quarantined island off the coast.

The Kŭrtz brothers were amongst the healthy passengers escorted to the courthouse in Philadelphia. They appeared before the mayor to swear loyalty to the Proprietor of Pennsylvania, William Penn, and to the British sovereign, King George II. (It was still several decades before the Revolutionary War.)

Northkill, the outermost settlement

Hans and Stefan purchased adjoining farmland in Northkill, Berks County, which was at the outermost edge of the settled regions where land was the cheapest and not yet cleared for farming. Northkill was regarded as the first Amish Mennonite settlement in America; however, various documents imply the region had an ecumenical mix of many religions worshipping together. Pennsylvania was, after all, William Penn’s “Holy Experiment”—a safe haven where all religions were respected.

Both Hans and Stefan married within the Northkill community and started their large families. Hans and Elizabeth (Rickenbach) Kurtz had eight children, whose births are recorded in the second tier of inscriptions of the 1580 family Bible. (For some reason, no other entries were added after that generation.)

Stefan and “Frena” (Yoder) Kurtz married in 1748, four years after he landed. The birth records of their eleven children are the first tier of inscriptions made in his 1744 Bible. There are two more generations, or tiers, recorded by their descendants.

Seven Year’s War and the Northkill Massacre

The massacre of 1757 was a shocking event in Northkill, when some members of the Hochstetler family were killed and three were abducted by a band of indigenous warriors. Up to that time there had been peaceful coexistence between the European immigrants and the indigenous Lenape Nation, who extended hospitality to the Mennonite and Amish farmers moving into their lands.

Court records, however, show grievances about boundary violations were filed by indigenous leaders as the great influx of European immigrants prompted settlers to expand westward. Tensions mounted by mid-century.

A European conflict between France and England precipitated the Seven Years’ Wars in America. The French garrisoned at Lake Erie, 300 mi. from Northkill, hired indigenous warriors to attack border towns along the Blue Ridge mountains. Northkill was one of them. The community never fully recovered, and many families moved to the safety of larger towns. Both Hans and Stefan moved their young families to towns miles from where the attacks had happened.

Womelsdorf and Myerstown, PA

Hans and Elizabeth Kurtz farm. The Kurtz Cemetery lies (right of barn) near the distant treeline.

Hans and Elizabeth established their new homestead in Womelsdorf, Berks County. Stefan and Frena and their four children under the age of seven settled in Myerstown, only a few miles from his older brother. Both of their original homes are still in use today. Hans and Stefan each served as Amish Mennonite deacons in the Conestoga Valley community.

Hans Kurtz was often referred to as “John” later in life. His tombstone reads “Johannes Kurtz.” He died at 74 years of age in 1796, just two months after his wife Elizabeth passed. They are both buried in the Kurtz Cemetery on their farm in Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania. His descendants continued farming this homestead for more than 230 years. It is not known when his family’s 1580 Bible was donated to the historical archives in Lancaster.

Stefan Kurtz, my direct ancestor, died at age 49 on April 12, 1773. His will, recorded 18 months earlier, stated his widow Frena (Veronica) shall have his whole estate in her hands, and he expressed hope that she would be able to keep their children together.

Frena gave birth to their last child, Sarah, two weeks after Stefan died. It seems with the help of their six older daughters, Frena was able to keep the family together. Family records say that both Stefan and Frena were buried on their farm, but their headstones were unreadable by the 1980s, when members of our family visited Myerstown.

One of their sons, Stefen Kurtz (1767), who was only six when his father died, took over the Myerstown farm fifteen years later when his mother, Frena, died in 1788. He inherited the 1744 Bible. His wife, Elizabeth (Yoder), gave birth to twelve children, recorded in the second tier of inscriptions in this Bible.

Their son, Jacob (1800), inherited the 1744 Bible next. He and his wife, Catherine (Gibble) recorded eleven children’s births in the third and final tier of inscriptions. My great-grandfather, Johannes Kurtz (1831), is listed in this generation.

When Jacob and Catherine Kurtz moved westward to Suffield, Portage County, Ohio in

1854, the family’s 1744 Bible came with them. Ten of their children piled into the Conestoga wagon, pulled by a team of four horses. A family diary says Johannes and his older brother Abraham helped to drive the wagon on the 6 week-journey.

The story goes that a valuable horseshoe was lost on the way, and young Johannes was sent back to find it. He was lost for two days, but eventually found his way back to the family wagon with the horseshoe. The brick home Jacob and Catherine bought still stands in Suffield.

Ending with a Twist

The tale of two Bibles has a recent new development. On May 3, 2023, I donated the Stefan Kurtz 1744 Bible to the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, which is a part of the Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania, only a few miles from where Stefan and Hans are buried.

The director of the Young Center, Steve Nolt, was interested to hear of Hans Kurtz’s older 1580 Bible in Lancaster. By coincidence, he had just learned that the historical society in Lancaster was deaccessioning many artifacts. In the weeks that followed, Steve was able to procure the Kurtz Family 1580 Froschauer Bible from the historical society.

Finally … 279 years after the two Bibles crossed the Atlantic together on the Muscliffe Galley, they are side-by-side again!

~ K. L. Kurtz, December 22, 2023

Photo by Steve Nolt, Director of the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies

Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies information can be found here.

Anabaptist History*

Other Blog pieces related to Kurtz Ancestry:

A brief Anabaptist History* (click left)

The Anabaptists ( or taufers in Swiss vernacular, which translates as "re-baptizers") were a rapidly growing group that separated from the Swiss Reformed Church in the 1520’s. They called themselves Swiss Brethren. However, the term"Anabaptists" became a negatively-charged, general label throughout Europe given to several "radical" religious groups who had some beliefs in common, especially the idea of adult baptism, rather than infant baptism. Swiss Anabaptists also believed in pacifism and felt that the state should not merge with the church and make final rulings on religious matters. The Swiss Reformed Church, which became a state church in major cantons of Switzerland, was instrumental in the heinous tortures, exiles, and death sentences for Anabaptists. The persecution continued more than 250 years. There have been reconciliation efforts extended to Anabaptists on behalf of the Swiss Reformed Church and Swiss government within recent years.

Comments